Speaking up for spoken word poetry

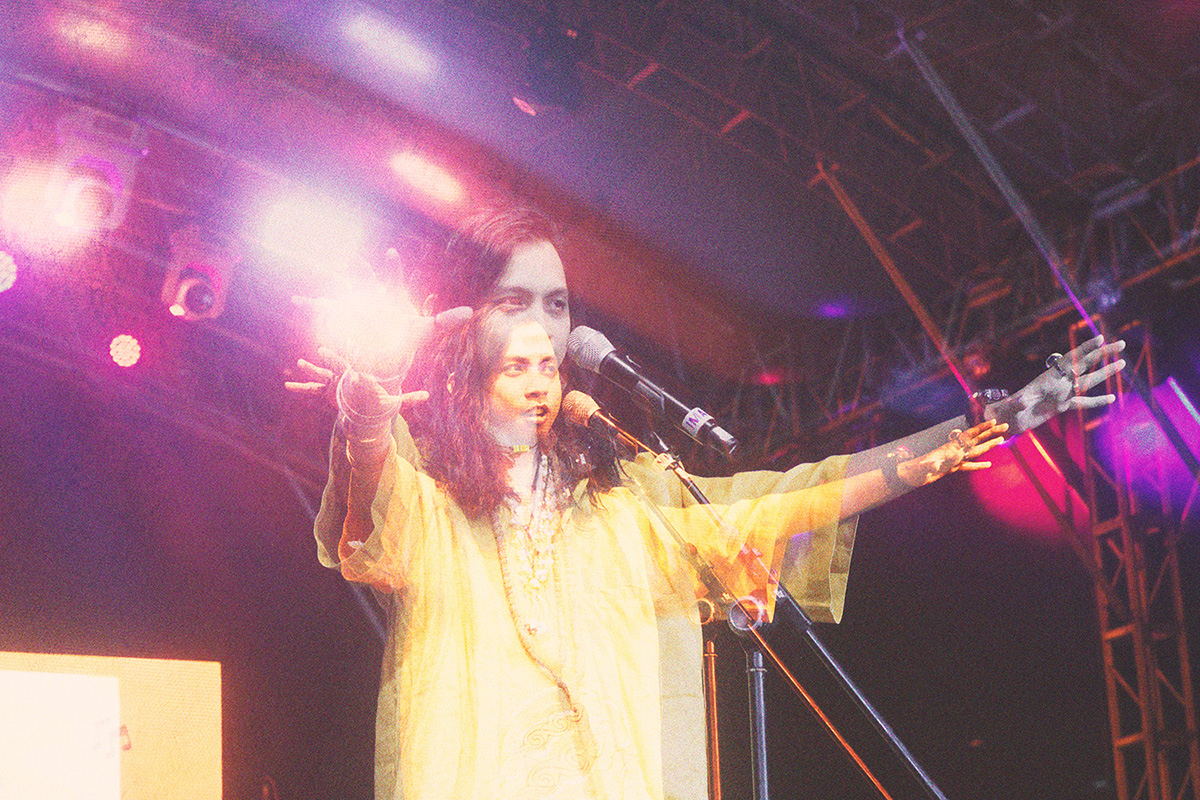

Championing spoken word poetry was never part of the plan for Leandro Reyes, a former HR professional. Now, he is the art form’s biggest advocate.

By September Grace Mahino

April 10, 2025

It’s calming to listen to Leandro Reyes speak. Even when he’s passionately distinguishing spoken word poetry from other types of performances, his mellow voice and thoughtful way of speaking keep his explanation from devolving into a pedantic diatribe.

“Technically, spoken word poetry, declamations, and monologues are all spoken words, right?” he begins. “But spoken word poetry claims ‘spoken word’ in its name because the art form needs it; otherwise it’ll just be the written poem, or poetry reading when read aloud.” He then explains that while declamations are statement-driven performances and monologues are heavy on the acting, spoken word poetry’s main ingredient—as its name also clearly states—is poetry. “So for a piece to be called spoken word poetry, it has to be poetic, or at least predominantly poetic.”

There’s nothing grandstanding about Reyes’ show of knowledge. It’s simply generosity borne from a deep love for the art. It’s the same love that pushes him to step up as its biggest advocate, serving as a community organizer, mentor, and representative. “My friends can attest to how obsessed I am with spoken word poetry,” he says. Aside from hosting Third Thursdays, an open-mic night for performances and general poetry discussions held every third Thursday of the month at The Globe Tower in Bonifacio Global City, and organizing workshops, he also answers questions about the art form on Instagram, all in service of making it more accessible to the general public.

Accessible, in this case, means having a wealth of credible information to draw from since Filipinos are already familiar with spoken word poetry. “It isn’t really an original art form here, unlike, say, balagtasan,” Reyes says, referring to the classic Filipino form of debating by way of verse. “It only hasn’t been properly established yet, with an understanding of what its fundamentals are.” There’s no lack in terms of talent and opportunities to develop them, as shown by the art form’s initial rise in the country during the late 2000s, spearheaded by the likes of Vim Nadera, Lourd De Veyra, and Kooky Tuason, and its hugot-predominant resurgence in 2015. Reyes knows it takes more than popularity for it to achieve permanence, though.

“When you want to learn how to do standup comedy, you know where to go. But aside from joining shows like Third Thursdays, what material do you pick up as a young poet? You’d likely go to YouTube where the content’s credibility is views-based. Like, if a spoken word poetry video has 7 million views, the probable conclusion would be, ‘This must be the epitome of a spoken word poetry piece.’ Then the appreciation for the form loosens.”

Reyes’ ease with being a visible and outspoken figure in the local spoken word scene belies an innate shyness. Before getting into theater, he was a quiet kid who shied away from the pressure of his family’s legacy. He is, after all, the great-grandson of Severino Reyes, the prolific writer and playwright behind the pen name Lola Basyang whose anthology of short stories, Mga Kuwento ni Lola Basyang, inspired adaptations in different forms of media. Turns out, similar to his progenitor, Reyes presents well through a persona, which is what theater offered to him. “There, I was no longer shy. I no longer felt alone.”

Unfortunately, post-college theater opportunities were slim so Reyes had to “let theater slip through [his] fingers.” For a while, he worked in the corporate world as an HR practitioner until he stumbled upon spoken word poetry—or rather until it found him. “It was like a boomerang,” he recalls. “Like, ‘This is how it feels, the community and belongingness that storytelling fosters.’” He promised himself that, unlike theater, he would never let it go.

One of his oft-used analogies to illustrate the value of understanding spoken word poetry’s basics is the lugaw-lomi example: “My friend claims to cook lugaw well. One day, they served me lomi, saying, ‘This is lugaw.’ The lomi tasted good, don’t get me wrong, but I couldn’t appreciate it fully, because when they called it lugaw, I expected to eat lugaw.” Reyes believes labeling an art form properly comes before everything since it defines the limits. “How would you stretch its limits if you don’t know what they are?” he asks rhetorically. “If you’re not doing proper research, not standing on the shoulders of those who built it, you’ll find it difficult to grow.”

Reyes has a full plate, what with the weekly spoken word poetry programs he hosts with Collaboratory, the upcoming second leg of his Bungad Tour with performance poet Mai Cantillano, and crowdfunding for the release of his first complete collection of poems, An Abundance of Such and Such. He’s also deep in drafting the guidelines on Filipino spoken word poetry that organizers from the academe and private institutions can follow when holding competitions. “It’s to eliminate the guesswork,” he explains. “It’s not stern at all, it’s just laying the groundwork. Later on, people can build on it, flip it, whatever, but at least they’re starting from somewhere.” Reyes is also talking to colleges and universities about establishing academic programs for spoken word poetry so the art form can develop scholars just like other literary disciplines.

“In another world, there’s somebody else doing all of that,” he admits. “But in the real world, nobody is. And my discomfort with that is heavier than my discomfort with taking on that role.” Advocating for spoken word poetry was never his plan, but Reyes doesn’t want the opportunity he has to slip by. “Spoken word poetry in the Philippines is at a unique point: Either we break through—or stay as is, operating on guesswork and each artist doing their own thing. It’s not bad per se, but I feel that without putting things into order, the permanence of the art form is at risk. And I’m not comfortable with that.”

With calm conviction, he concludes, “If I die fighting for the establishment of spoken word poetry within the Filipino context as an art form everybody knows, I’ll die happy. Every day, that’s what I try to do.”

***

Follow Leandro Reyes ( @lrbasyang ), Collaboratory.PH ( @collaboratory.ph ), and Third Thursdays ( @lrthirdthursdays ) on Instagram and subscribe to his YouTube channel The Basyang Kid to be updated on his projects and spoken word poetry events and programs. Lead image by Kam Orgasan.

Want to connect with Leandro? Get in touch with CREATEPhilippines. Email us at [email protected]. Want to be part of our creative community? Sign up and register for our Directory of Creatives here.