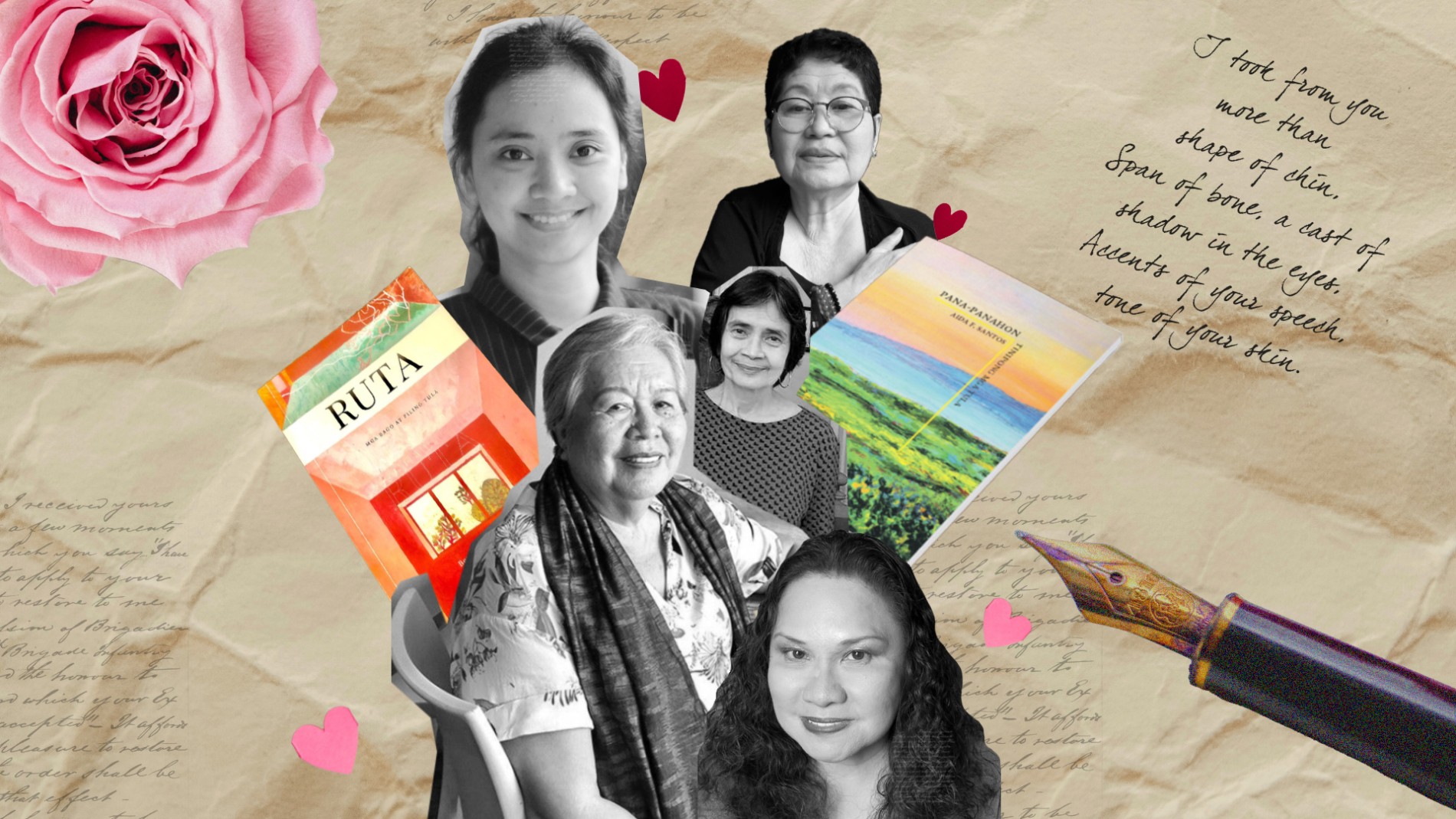

Motherhood in the poetry of 5 Filipina creatives

By Arry Asiddao

May 06, 2022

Poetry can articulate even the most complex human experiences. A string of words can provide a different point of view or a deeper understanding, making the experience a lot more valuable when it is written.

This Mother’s Day, we give you five poems that capture the most intimate moments and depict the unique and shared truths of motherhood, through the words of Filipina creatives.

1. Multi-awarded poet and retired professor Merlie Alunan’s My Mother traces the ties between a mother and her daughter, starting from the infant in the mother’s womb, to the physical features of the mother retained in the child, and the ancient fears of childbirth inherited from generations of women before them. Towards the end of the poem, the narrator hints at breaking free from the traditional sense of motherhood.

My Mother

Merlie Alunan

Your womb described my earliest space--

Terse measure in pulses of our one blood,

The flow and turning of my fetal days.

I took from you more than shape of chin,

Span of bone, a cast of shadow in the eyes,

Accents of your speech, tone of your skin.

It was your law whipped my conscience

Recalcitrant as hair loose in a wild wind

To strict conformity and terrible obedience.

Your unrepentant fears cower inside me

Shivering their dread of birth, danger

Ancient as the grave's wait for its fee.

It is your shelter I had yearned to fly,

Startling to the doom written in the blood,

The statement of our common destiny.

Watching you now inside this shrunken room,

Your skin a loose bag over your brittle bones,

I think how flight would only bring me home.

2. Awit ng Labandera presents a harsh but candid depiction of a mother’s burden to provide and care for her children. It takes the perspective of a mother trying to get her child to sleep, while also expressing her exhaustion from working all day. The poem’s last stanza illustrates through the imagery of doing laundry how poverty traps mothers into a cycle of working, resting, and hoping. The poet behind this poem, Palanca awardee Aida F. Santos, is a human rights advocate and known feminist.

Awit ng Labandera

Aida F. Santos

Matulog na bunso, maikli ang gabi

Itong abang ina’y bigyan ng pahinga

Ito ngang tatay mo’y laging nangangati,

Kahit maghapon nang ako’y naglalaba.

Matulog na bunso, marami ang lamok

Kamay ko’y ngawit man, ika’y papaypayan;

Diwa ko’y ibig nang manghina, malugmok

Sa kakukusot ng ating kaabhan.

Matulog na bunso, wala ka nang gatas

Mabuti’y ipikit ang mata’t mangarap,

Sa buhay na itong panay na lamang malas

Baka sa pagtulog, may dulot na sarap.

Matulog na bunso, mahaba ang araw

Kailangan ko pang mag-ipon ng lakas,

Muling babanlawan, palad tang mapusyaw

Ikukulang muli ang gusgusing bukas.

3. Atong and his Goodbye paints a simple but poignant scene of a mother parting with her child at school. By describing the scene in piercing detail, esteemed poet Benilda S. Santos successfully communicates the universal sense of loss and longing that comes with realizing that one’s child is growing up and changing.

Atong and his Goodbye

Benilda S. Santos

Translated by Ramón C. Sunico

It is no longer as it once was

when there was no end to his waving

to his trailing looks

until I turned the corner

toward the school's gate.

It is because five years have passed.

The short pants are gone.

Now his slacks

must always match

his shirt, tucked-in,

and, complete with sideburns, his hair

parted neatly at the right.

When I say

"Okay son. Goodbye,"

his standard reply's

a tight smile

an eyebrow's twitch

or sometimes

the slightest of nods.

Nothing remains of the old goodbyes.

And when this happens to the mother he leaves behind

the wind blows through her though there is no breeze.

Here in the car, everything spins

though my foot is on the brake

And I shiver though the sun burns

fiercely on the streets.

4. Poet and playwright Ma. Cecilia “Maki” de la Rosa’s Timang reads like an oyayi, a traditional Filipino lullaby for children. While exuding tenderness, it also reflects the narrator’s anxieties for her child, with sleep representing the carefree days of childhood that the mother encourages her child to relish.

Timang

Ma. Cecilia de la Rosa

Itulog mo nang mahimbing

ang iyong pagiging bata.

Baunin sa paglalakbay

ang pagiging malaya;

habang mga paa lamang

at hindi pa ang puso

ang hinahamon ng mga sangandaan,

ilakad, ihakbang, itakbo

sa mga lambak at gulod

ng panaginip ang malilinggit,

malilikot mong talampakan.

Sa ibabaw ng mga ulap,

iapak ang galak at ‘wag matakot

ibagsak ng ulan.

Sa baha’y sasaluhin ka ng tuwa

sa ‘di mo pa nakikilalang mga sigwa.

Pagmamasdan ko sa lamlam

ang ngiti mong ‘di pa nagmamalay

sa silid na walang imik, pakikinggan

ang mahinang halakhak at mga pangungusap

na walang kahulugan.

‘Bayaan mo akong maging saksi

habang sa dis-oras ng gabi

ay ‘di ka pa ginigising ng lumbay.

Habang ganito, Anak,

ipaghilik mo muna si Nanay.

5. Joi Barrios-Leblanc’s Ang Pagiging Babae ay Pamumuhay sa Panahon ng Digma ties motherhood with the collective struggles of women. To a mother, according to Barrios, being in a war means struggling to feed your children. This struggle does not only lie in preparing their next meal, but also in worrying– echoing the constant state of fear and apprehension that women experience. The poem ends in empowerment and realization that ultimately, being a mother and a woman means constantly fighting and asserting your place in society.

Ang Pagiging Babae ay Pamumuhay sa Panahon ng Digma

Joi Barrios-Leblanc

Ang pagiging babae ay pamumuhay sa panahon ng digma.

Kapiling ko sa paglaki ang pangamba,

hindi ko tiyak ang bukas

na laging nakakawing

sa mga lalaki ng aking buhay:

ama, kapatid,

asawa, anak.

Kinatakutan ko ang pag-iisa.

Sa pagiging ina,

kaharap ko’y tagsalat.

Pagkat ang lupit ng digmaan

ay hindi lamang

sa paggulong ng mga ulo

sa pagguhit ng espada,

kundi sa unti-unting pagkaubos

ng pagkain sa hapag.

Ay, paano sabay na magpapasuso sa bunso

habang naghahanap ng maisusubo

sa panganay?

Walang sandaling

walang panganib.

Sa sariling tahanan,

ang pagsagot at pagsuway

ay pag-akit sa pananakit.

Sa lansangan,

ang paglalakad sa gabi’y

pag-aanyaya sa kapahamakan.

Sa aking lipunan,

ang pagtutol sa kaapiha’y

paglalantad sa higit na karahasan.

Kay tagal kong pinag-aralan

ang puno’t dulo

ng digmaan.

Sa huli’y naunawaan,

na ang pagiging babae

ay walang katapusang pakikibaka

para mabuhay at maging malaya.